I Am Never Buying Anything From the Internet Again

Nineteenth-century retailer John Wanamaker is responsible for perhaps the most repeated line in marketing: "Half the coin I spend on advertising is wasted, the trouble is I don't know which one-half."

Today, marketers are grappling with the Wanamaker Paradox: The more we learn which one-half of advertizement is working, the more we realize we're wasting way more than than one-half.

Perhaps you're nodding your caput about at present. Most people you lot know don't click online ads. At least, not on purpose. But at present research is getting closer to quantifying exactly how few people click on Cyberspace ads and exactly how ineffective they are. It's not a pretty picture.

The Problem With Search

Have search ads, which have helped Google get the richest advertizing company in the history of the world. Search ads are magic, in a way. Throughout history, most ads have been imprecise branding. Y'all're watching TV or reading the paper, and you're interrupted by marketing—Samsung's new thing is shiny;Ford F-something-something can bulldoze through dirt; Apathetic blah apathetic GEICO—that has the staying power of a snowflake in an oven. Simply search catches consumers at the moment they're actually looking for something. It shrinks the famous "purchase funnel" to its final stage and gives us tailored answers when we're asking a specific question.

That's the theory, at least. Merely a new controlled study on search ads from eBay research labs suggests that companies like Google vastly exaggerate the effectiveness of search.

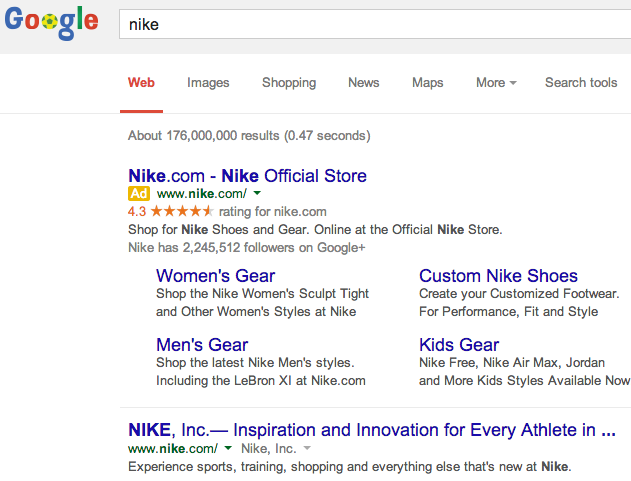

For example, consider what happens when I wait upwards a brand, like Nike. An advert for Nike.com appears just above an organic link to ... Nike.com.

Campaigns similar this take "no measurable short-term benefits," the researchers concluded. They merely give consumers a perfect substitute for the link they would have clicked anyway. (The only mode it would add together value is if Nike is paying to keep a rival like Adidas out of the top slot ... assuming Google would sell Adidas the top sponsored link on searches for "Nike").

But what virtually more common searches for things like "purchase camera" or "best cell phone," where many dissimilar companies are bidding to answer our queries? A well-placed search ad ought to grab curious consumers at the peak of their interest.

Simply in a study of search ads bought by eBay, the most frequent Internet users—who run into the vast bulk of ads; and spend the most money online—weren't any more than likely to purchase stuff from eBay later seeing search ads. The study concluded that paid-search spending was ironically concentrated on the very people who were going to buy stuff on eBay, anyway. "More frequent users whose purchasing behavior is not influenced by ads business relationship for most of the advertizement expenses, resulting in average returns that are negative," the researchers concluded.

'I Was Gonna Buy It, Anyway'

I'm not fully convinced that search ads are every bit ineffective as this paper suggested. To their credit, the authors admit that other studies most Google have found search to have higher ROI.

But the big thought behind their research is powerful. Academics call it endogeneity. We can telephone call information technology theI-was-gonna-purchase-it-anyhow problem. Some ads persuade u.s.a. to buy. Some ads tell us to purchase something we were already going to buy, anyway. Information technology's awfully hard to figure out which is which.

Enter Facebook, the 2nd-biggest digital advert company in the U.S. Just as Google is synonymous with search, Facebook is ubiquitous with social. The News Feed is the most sophisticated content algorithm ever. The company represents the spine of so many apps and sites that it tin can marshal an astonishing (and growing) amount of data nigh us.

While Google can catechumen consumers at the bottom of the purchase funnel, Facebook is more than like TV, a diffuse broadcast of stories where some companies hope to interrupt our lazy attention with branding letters. In 2012, Facebook partnered with Datalogix, a house that measures the shopping habits of 100 million U.S. families, to see if people who went on Facebook and saw ads for, say, Hot Pockets, were more than likely to go out and purchase Hot Pockets. According to Facebook's internal studies, the ads weren't getting many clicks, only they were working brilliantly. "Of the kickoff 60 campaigns we looked at, lxx percentage had a 3X or better return-on-investment—that means that 70 percent of advertisers got back three times as many dollars in purchases as they spent on ads," Sean Bruich, Facebook's head of measurement platforms and standards, told Farhad Manjoo.

There are a few reasons to be skeptical when Facebook concludes that its ads are working spectacularly. First is the bones B.S.-detector clarion inside your soul saying you shouldn't automatically believe companies who say "our research has apparently concluded unambiguously that we are awesome." Facebook, ad agencies, and ad consultants all do good from more ad spending. These are non objective parties.

Second, there's that peskyI-was-gonna-buy-it-anywaybias. Let's say I desire to buy a pair of glasses. I live in New York, where people like Warby Parker. I've shopped for glasses at Warby Parker'south website. Facebook knows both of these things. And so no surprise that today I saw a Warby Parker sponsored postal service on my News Feed.

Now, let's say I buy glasses from Warby Parker tomorrow. What can nosotros logically conclude? That Facebook successfully converted a auction? Or that the many factors Facebook considered earlier showing me that ad—e.g.: what my friends like and my past shopping behavior—are the aforementioned factors that might persuade everyone to buy a pair of spectacles long before they signed into Facebook?

Mayhap Facebook has mastered the art of using advertising to convert sales. Or maybe it's mastered the fine art of finding people who were going to buy certain items anyhow and showing them ads after they already fabricated their decision. My bet is that the answer is (a) somewhere in the middle and (b) devilishly hard to accurately measure.

Also Much Information

The eBay study suggested that people who click well-nigh ads aren't beingness influenced.

The Facebook report suggested that people who are being influenced aren't actually clicking ads.

It makes you wonder whether clicks affair, at all.

In fact, in that location's reason to wonder whether all advertising—online and off—is losing its persuasive dial. Itamar Simonson and Emanuel Rosen, the authors of the new book Absolute Value, accept an elegant theory almost the weakened state of brands in the information age. Corporations used to have much more control over what kind of information consumers could discover near their visitor. The bespeak of advertizement was stronger when information technology wasn't diluted by the sound pollution of the Cyberspace and social media.

Think near how much you can learn almost products today before seeing an advertisement. Comments, user reviews, friends' opinions, price-comparison tools: These things aren't advertising (although they're just as ubiquitous). In fact, they're much more powerful than advertizement because we consider them information rather than marketing. The difference is enormous: We seek information, and then nosotros're more than likely to trust it; marketing seeks us, so nosotros're more likely to distrust it.

Simonson and Rosen share an chestnut from 2007: X thousand people around the globe were asked if they'd want a portable digital device like the iPhone. Marketplace enquiry concluded that at that place wasn't sufficient demand in the U.Southward., Europe, or Nihon for an such a device, because people liked their cameras, phones, and MP3 players besides much to want them mushed into ane device. Today the iPhone is the most famous telephone in the world, not just because its ad campaign was and then groovy, but because the user reviews of the telephone were overwhelmingly positive and and so widely disseminated.

Measuring and predicting individual purchases has never been easy. But measuring and predicting how everybody'southward buy is affecting everybody else's shopping behavior in the Panopticon of the Internet is practically incommunicable.

The Internet was supposed to tell united states of america which ads work and which ads don't. Instead, it's flooded consumers' brains with reviews, comments, and other information that has diluted the ability of advertising. The more we learn about how consumers brand decisions, the more than we larn nosotros don't know.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/06/a-dangerous-question-does-internet-advertising-work-at-all/372704/

0 Response to "I Am Never Buying Anything From the Internet Again"

Post a Comment